|

Dr Geoffrey Hull

source: Wikipedia.org |

Once every now and then one finds an author capable of approaching a daunting subject with remarkable clairvoyance, not muddling himself among polemics or minutiae. Dr. Geoffrey Hull is one such author. His The Banished Heart: Origins of Heteropraxis in the Catholic Church recalls that old saying that the truth is not between two positions, but rather above them. Hull examines the roots of the twentieth century liturgical overhaul by rising above the disputes between liberals and traditionalists that have raged on for five decades and taking a long, far-sighted look back centuries more, to the late first millennium, when the Roman liturgy was maturing, the Roman patriarchate was expanding its missionary presence in Western and Eastern Europe, and the Papacy's prestige and power were expanding well beyond the walls of Rome. How and in what context did the Roman liturgy change from a theocentric, organic act of worship to an anthropocentric fabrication? The Banished Heart is a thorough, insightful answer to this question.

The Basic Argument

The answer to the aforementioned question, developed over 356 pages, is found in an epigraph at the beginning of the second chapter. He quotes the 19th century Russian ascetic Theophan the Recluse: "You should descend to your heart from your head... The life is in the heart, so you should live there. Do not think that this applies only to the perfect. No, it applies to everyone who begins to seek out the Lord." The Roman rite of the Catholic Church began to live more and more in its head rather than in its heart, which is its holy liturgy. Hull traces two closely intertwined trends that emerged as characteristics of the Roman Church:

An emphasis on rationality and logic that descends from the Roman legal tradition and which survived in the Latin Church's theological language

A tendency to imitate the secular forces of the time with regards to internal government and relations with those outside of itself (in this case, non-Latin Christians)

The second of these points became a problem when Charlemagne attempted, with reasonable success, to appropriate the Church into his Frankish kingdom and utilize Christianity as a means of state unification. So strong a unity with the state existed that the Greek routinely called the Latins "Franks" rather than "Romans" or "Italians" or "Germans." Toward the end of the first millennium and at the dawn of the second, the Roman Church began to equate itself exclusively with Christianity, supposing anything at variance with its own theology and liturgy to be suspect. This led to the virtual suppression of the Mozarabic rite in Spain, the attempted suppression of the Ambrosian rite in Milan, and tergiversations of language and rite in Eastern Europe. What was originally the Primacy of Rome became justification for uniformity, an obsession which plagues the Latin rite of the Catholic Church to this day.

|

The often-maligned rite of Milan

source: newliturgicalmovement.org |

This phenomenon continued well after the end of Frankish significance. Innocent III imposed the Latin liturgy on Constantinople after finding himself, unhappily, de facto king-maker of Byzantium. The Church's missionary efforts in this regard are also quite sad, as Hull demonstrates. Chapter 12 is a particularly difficult one to read. In it Hull recounts the visits of various Catholic missionaries to many branches of Apostolic Christendom which found themselves, either through historical circumstance or the sins of their fathers, out of communion with the Holy See. Many of these communities, often entire Churches, wished to re-establish communion with Rome. The "Thomas" Malabar Christians of India, the Chaldeans of the Middle East, and the Orthodox of Ethiopia all entered into inter-communion with the Roman Church and clergy, even giving Rome considerable leeway in local matters. Invariably a derisive attitude overcame the visiting clergy, who attempted to impose the Roman rite on these Christians and to end their own unique traditions, such as married priests. The local Churches rebelled and a small fragment, wishing to retain the Roman communion, would set up a "uniate" church, a church that would be held in contempt by both Rome and the local Orthodox. The disorder and disdain causes by Latinizations in Ethiopia were of such great magnitude that a Roman priest would be stoned to death without trial until the 19th century.

This narrow view was noxious alone, but with a few other influences it would become fatal. In earlier days the Eastern Churches maintained the heart of Christianity while Rome was its head. The loss of the Eastern Churches meant Rome would think itself the only legitimate expression of liturgy, of theology, and of the priesthood (disdain for married priests outside the Latin rite continued into the 20th century). There could be little introspection possible in such an environment.

Which returns the reader to the first point: rationalism. Everything would henceforth conform to Roman rationalism. Although the book is largely about the danger of excessive rationalism, Dr. Hull provides no strong definition, but it might suffice to say that the author means the idea that all matters, human and Divine, must be reduced and explained according to human reason. Human reason eventually became a standard by which other facets of the faith were to be judged and expressed. Prosper of Aquitaine's dictum "Lex orandi legem statuat suplicandi" was the common belief of all Christendom at one point. Liturgy was the theologia prima, the primary study and expression of faith in the mysteries of Our Lord. But as the Church began to enter secular endeavors her theological language became more and more legalistic. Scholasticism is an accurate and clear system, but it is also a system born out of the words and thought process of the pre-Christian Roman Law. When written theology began to supplant liturgy concepts became fungible. Many movements in the Middle Ages, Hull aptly proves in Chapter 4, were anti-rational: the Nominalists, the Franciscans, and the Scotists all diminished reason's capacity to understand the Divine. The Counter-Reformation would see rationalism return with renewed vigor: primary consideration drifted from elegance to validity, from worship to instruction.

Yet the liturgy survived the East-West schism intact. Even under the auspices of Papal primacy, Rome was less and less able to alter the local rites of given dioceses and Rome, although convinced of the theological superiority of her rite, often had to defer to the local usages. All that ended with the Protestant Reformation.

The Reformation

Hull acknowledges the irony that the Reformation began as a reaction to a perceived idolatry, the Renaissance era Roman Church's emphasis on philosophy and human reason. Dr. Hull does not state this observation, but readers should find another irony in that, aside form Luther and Cranmer, most all the major Reformers were lawyers.

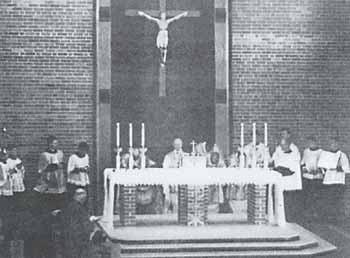

|

Chiesa Gesu in Rome, home of the Society of Jesus.

Notice the great nave and tiny sanctuary with

no choir.

source: Wikipedia.org |

The Reformation essentially privatized religion, making faith a matter of private piety and Scriptural study. What is most perplexing is that the Church, in combatting Protestantism's heresies, followed the same spirit and pattern. The adoration of the Blessed Sacrament, devotions deriving from private revelations, Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament, and the reception of the Sacraments more often than not became matters of personal, private spirituality. The greatest force during the Counter-Reformation was the Society of Jesus which, Dr. Hull reminds readers, was the first religious order ever to not sing the Office in common every day. The purpose of the Jesuits was to promote the basic teachings of Catholicism, which they did quite well. What they did not do was promote the Catholic spirit. The Jesuits succeeded in building universities and parishes, in instructing millions and even in creating their own operatic genre. Yet they did not re-kindle the liturgical understanding of the faith that had existed from the earliest days of Christianity until the 16th century.

The religious pluralism that resulted from the Reformation often meant that Catholicism was not as keenly defended by the ruling authorities as in previous times. Indeed, rather than the secular defending the spiritual, the spiritual took on the ethos of the secular. Baroque churches, with reredos that look like stone curtains and altars as close to the rail as can be, in some ways resemble theaters of the same era more than they resemble churches of a few centuries prior (161). Consequently, the liturgy became either a time for private prayer or a great Italian opera. Indeed, Voltaire called the Mass the "opera of the peasants."

The sad conclusion one reaches at the end of Chapter 10, called "Reformed Catholicism," is that the Counter-Reformation failed to reach its goal of re-converting Europe. Secular revolutions sprang up, one after another, promulgating and promoting humanist, socialist, democratic ideals far removed from Christianity. The liturgy fell into disuse. A cult of personality, called Ultramontanism—which survives to this day, developed around the Pope. The Church had made herself the religion of the majority of persons in Europe. It is little wonder that with such a pious, rationalistic outlook the gaze of the theologian's eye would eventually turn inward.

Setting the Stage and the Featured Presentation

The Banished Heart recounts various moments in the development of the Liturgical Movement: the Jansenist movement's demands for more focus on the laity, for simplification, and for rubrics that conformed to their own standards, all supposed features of a more primitive, purer liturgy. The movement culminated in the robber-council of Pistoia, condemned by Pius VI in 1794.

Whereas many traditionalist writers often focus on the Modernist heresy, Hull spends more time connecting the proverbial dots between Jansenism—an outgrowth of rationalistic Protestantism—and the left wing of the Liturgical Movement. After the condemnation of Modernism by St. Pius X in Pascendi many would-be Modernists began to study more benign subjects, such as liturgy. Here the Liturgical Movement underwent a fundamental change. Initially it had intended to restore full use of the Roman liturgy, as opposed to the low Mass and a Rosary variety that existed at the time. Suddenly it took on a "pastoral" aspect interested in the needs of "modern man." Pius XII's reversal of Prosper of Aquitaine's dictum, the immovable baroque mindset of the Curia, the dynamism of the Modernist movement, and the election of John XXIII all but guaranteed serious liturgical change.

Much has been made of the process of constructing the new liturgy, so we shall not recapitulate it here. Dr. Hull adumbrates accounts of the first celebration of the Novus Ordo Missae for the Synod of Bishops in 1967 and three celebrations for the Roman Curia (one low, one high, and one low with music). All three were in vernacular and, possibly, versus populum.

|

| Archbishop John Ireland |

Another effect of the Reformation Hull does not neglect was the founding of the United States of America, which is given all of chapter 14 (Pax Americana). The materialistic outlook of American society and the focus on the individual impacted the practice of the faith in the United States, the author suggests. In light of Bishop Carroll of Baltimore and Archbishop John Ireland's outright jingoism, one would be hard pressed to see matters otherwise. Hull's outlook on the United States' culture can be summed up in these two sentences: "In the American philosophy man's highest purpose is to assert his 'inalienable right' to 'Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness' on earth. Eternal life is an optional extra for those who choose to believe in it" (238). America's tremendous wealth allowed American bishops and theologians to leverage their influence on a Vatican in dire need of funds to rebuild a Church decimated by war. This took the form of Dignitatis Humanae and seats on the various liturgical commissions.

Other Points

The Banished Heart, which is laid out by theme rather than by chronology, touches on several other points that did not fit into the structure of the above summary:

Roman centralization's effects on local languages: there are dialects of Spanish and Italian which are not available in the new liturgy, forcing locals to worship in a language that may be considered outside of the community. A more serious example might be the near extinction of the Irish language at the hands of clergy who thought speaking it a sin.

Obedience was made into a worthy end in and of itself rather than a means of living an un-complicated life, as it was originally intended. The author has some especially strong words for those who equate the Pope's words and actions with the immediate inspiration of the Holy Spirit. Dr. Hull passes some comments about John Paul II that I dare not repeat here.

- The Banished Heart presents a realist assessment of the work of Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, the controversial French prelate who founded the Society of St. Pius X and consecrated four men to the episcopacy without canonical approval. The Banished Heart acknowledges that while Lefebvre kept the pre-Conciliar liturgy alive the right wing political affiliations of the SSPX also contributed to making the 1962 rite a "ghetto" rite until 2007. Still, Dr. Hull asks, why was Lefebvre the only noticable dissident of any degree or of any kind punished after Vatican II? Lefebvre's work, sometimes good and sometimes bad, retained some semblance of continuity with the Church's past, which is exactly why he drew the ire of Paul VI and John Paul II.

- The author relies heavily on Eastern Orthodox liturgists and theologians, as the East, whatever their problems, have retained the primacy and importance of liturgy as the theologia prima better than the Western Christians have. Many traditionalists will undoubtedly find this point discomforting and some may even accuse Dr. Hull of swallowing Orthodox glorification of the liturgy, as this one fellow does, but this canard lacks merit. Eastern theologians rarely think of anything new. Their most recent theological movement was the Hesychast revival of the 14th century, in itself a reiteration of 5th century theology. Byzantine liturgical theology is not made illegitimate by the faults of the Popes and Patriarchs.

- The negative reaction to Summorum Pontificum was an internal dispute between two segments of the revolutionary party within the Church, not between "liberals" and "conservatives." Josef Ratzinger, who maintains that he never revised his views, was a proponent of the "new theology" in the 1950s and 1960s. His interest in the 1962 rite and in Archbishop Lefebvre's Society of St. Pius X derives from his pluralistic world view and his wish to have come to lasting peace with the French prelate in 1988. His interest was not in a revival of the old liturgy per se. His opponents lacked his desire to find a solution for the Society of St. Pius X, but not his opinion that the new missal has brought good.

Shortcomings

On the whole this is the best book I have read in years on the current state of the Catholic Church, both liturgical and otherwise. Dr. Hull displays tremendous insight into liturgical theology, the history of the Papacy, the evolution of piety, the Church's relationship with secular culture, and the events of the 20th century, namely the Second Vatican Council. Toward the end of The Banished Heart Dr. Hull briefly relapses into the common mistake of seeing everything prior to the Council as a countdown to the Council. The Council's only document on the liturgy was a transitional one, written to justify more substantial reforms that had yet to come. Banished Heart only briefly touches on this point, instead adopting the familiar line that the reforms betrayed the Council's modest wishes.

Another shortcoming is an omission. The Banished Heart rightly asks why the Eastern Catholic Churches, if they are considered by the modern authorities to be as fully Catholic as the Roman Church, were given a separate document at Vatican II un-related to the document on the Roman liturgy. In short, the Eastern Churches were treated as a curiosity. Another point that could have been made is the dishonest, ecumenical use of Eastern theology in the post-Conciliar age. How often have we heard the term "full communion" when the hierarchy dialogues with Protestants, or Jews, or Muslims? The idea of being "in communion," a mostly Eastern concept, is defined as sharing Sacraments. None of the aforementioned groups have any Sacraments (although Protestants usually baptize validly). Yet "full communion" is normally implied to be lacking, as though a partial communion exists when it does not. This may not have occurred to Dr. Hull or it may have seemed tangential, but it was worth saying somewhere.

Lastly, and this is not a small problem, there is no working definition of the "traditional liturgy" in The Banished Heart. It is simply treated as something that exists. Dr. Hull passes over the 1911 Office reforms and 1955 Holy Week novelties with neutrality. The Roman rite surely suffered through these changes, but did the Roman rite not also suffer when various local rites, which preserved certain facets of the Roman liturgy which had fallen into disuse and contributed in other regards, became extinct. A firmer definition of the Roman liturgy's essential features and process of evolution would have made the last third of this book all the more forceful.

Conclusion

Dr. Geoffrey Hull's The Banished Heart: Origins of Heteropraxis in the Catholic Church tells the tale of how the East-West schism allowed the Church of Rome to be engulfed in its own tendency toward rationalism and to "banish its heart," the liturgy, from its head, making it ill-suited to deal with the Reformation and the political revolutions that followed. The book is thorough, readable, well researched, and not the conventional traditionalist polemic. This book will challenge many readers' preconceptions about liturgical theology, the Reformation, and the events leading up to the Second Vatican Council. But if readers are patient and genuinely wish to learn why the Roman rite underwent the revolution it did, then they should order a copy immediately.